Is The Princess Diaries Right-Wing?

Depends how you feel about Orléanism.

The Princess Diaries - you read the subtitle but you don’t know what Orléanism is? Okay, you know how the July Revolution - you know about the July Revolution, right? No? Okay, the French Revolution - you don’t want me to explain the French Revolution? You want me to get to The Princess Diaries? But, like, what do you know about the French Revolution? No, I’m genuinely ask- okay - no, I didn’t mean it like that, I’m sorry, it came out too strong, let me - it’s just that you can’t understand the July Revolution without - yes it really is relevant to The Princess Diaries, I’m sorry, I just have to - no, it won’t make any sense withou- I promise this is interesting, I’m sorry, just let me explain, I’m sorry.

The French Revolution

…which I know you already know about, again I’m sorry for telling you things you already know, went through a bunch of different political phases:

The pre-revolutionary era (Charlemagne to 1789), the Ancien Régime, under an Absolutist Monarchy, led by the House of Bourbon. Absolutist monarchies are exactly what they sound like: Systems of government where a monarch, usually a king, wields absolute power. This system may start failing if, say, you fight a global war and then fund a revolution overseas and then have crops fail all in quick succession, and you are also Louis XVI and you can’t budget your way out of owing a buddy $5.

The early stages of the revolution (1789 to 1792), a Bit of a Clusterfuck grasping at a Constitutional Monarchy, a political system that still has a monarch but where the monarch has a constitution limiting their powers. This was the goal of the moderate French liberals, all Ameriboos, gung-ho about property law and legislative bodies. Their biggest problems were that they spent all their time focusing on political reform and starting war with Austria instead of feeding people, and that notorious waffler Louis XVI decided he didn’t want a constitution, actually. This is around the point where my American public education stopped talking about the French revolution.

Because the king didn’t seem to really want reform, many began thinking that France should have a Republic with a very strong legislature (1792 to 1795) and no king whatsoever. The republic worked great except for:

The mass killing sprees of nobles and then anyone suspected of being an enemy of the Republic,

The wars that they kept fighting everywhere across Europe, including a civil war within France,

The completely dismal domestic economy outside of spoils from those wars (which, against all odds, the French were winning),

The attempts to replace Catholicism with a deeply off-putting civic religion invented from whole cloth,

The fact that they kept becoming more and more extreme, with a continuing cycle of legislators literally moving from the left to the right of the assembly halls as republican leaders killed off yesterday’s radical for being today’s arch-conservative,

The fact that the radical leader Robespierre made a speech saying he had a list of enemies within the highest levels of government and then didn’t share names, making everyone close to power think that they were up next to be killed, leading them to kill Robespierre first.

Once Robespierre’s head was fully detached from his body (1794), those still alive went about establishing a new form of leadership in the republic, a Directory (1795 to 1799), led by a Den of Vipers plainly hungry for raw power. Everyone hated the directory, but they hated Robespierre’s terror more, and they also liked a young general named Bonaparte who was out there winning France battles.

One of the vipers cut Bonaparte in on a self-coup. Bonaparte, knowing how to outmaneuver an opponent, used this opportunity to make himself First Consul of the Consulate (1799 to 1804), basically a military dictatorship with Roman trappings. Bonaparte would lean even further into the Roman trappings when he declared himself Emperor Napoleon I of the French Empire (1804 to 1814).

Napoleon swashbuckles his way through Europe but can’t pull off a land invasion of Russia. All of Frances’ allies become enemies, Napoleon gets his shit kicked in back to Paris, the Empire is abolished. The remaining powers of Europe restore the Bourbon monarchy and force it to adopt a very weak constitution, the Charter of 1814. Napoleon attempts a comeback. It works, lasting a little over three months, or (around) 100 days if you’re being poetic, before he loses at Waterloo and the powers of Europe restore the Bourbon monarchy again.

Okay, got it? Good. Now we can talk about the other French revolution.

The July Revolution

The liberal-minded Duke of Orléans, a cousin of the king (the House of Orléans being a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon) and potential heir to the throne, thoroughly supported the early stages of the revolution of 1789, becoming a favorite of the constitutional monarchists. The duke eventually abandoned his title, renamed himself Philippe Égalité, literally “Philip Equality,” and voted to kill Louis XVI. Robespierre cut Égalité’s head off in 1793, but his son Louis-Philippe escaped into exile. Louis-Philippe mended the rift with the senior Bourbons and returned to France upon their restoration in 1814.

The restored King Louis XVIII mostly respected the Charter of 1814. His brother, successor as king, and avowed reactionary Charles X had no such plans. On July 25, 1830, Charles, whose allies in the Charter’s mandated legislature were about to lose control, attempted to abolish the Charter by decree and restore full absolutism. Paris revolted.

Three days of blood and barricades later, days that would later be called “Glorious,” Louis-Philippe, under the revolutionary tricolor and over the objections of radical republicans, accepted accession to the French throne.

We now have our three great Monarchist traditions of the French right.1

Legitimists: Supporters of the senior Bourbon branch. Absolutists who, at their most extreme, want to restore feudal privileges the divine right of kings. Biggest supporters among the old aristocracy, the church, some of the more religious peasantry.

Bonapartists: Populists, militarists, big fans of centralized government. Major support from soldiers, ex-soldiers, and anyone who likes the idea of a ruler establishing himself through his own sheer might.

Orléanists: Constitutional monarchists. Liberal in the classical sense. Big on free trade and property rights, somewhat big on civil liberties. Generally well educated. Lawyers, doctors, merchants. Not rabble like those pesky republicans.

France would continue to revolt through the rest of the 19th century. Most notably for our purposes they overthrew Louis-Philippe in the other, other French Revolution, the February Revolution in 1848. The French, having overthrown a Bourbon king, then established a Second Republic, and then a few years later Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew overthrew the republic and established a Second Empire. Karl Marx saw history repeating itself and famously remarked, “What is this, a joke?”

What does this have to do with The Princess Diaries?

Disney’s The Princess Diaries is the most Orléanist movie franchise I have ever seen.

Yes, it’s also a book series, but I’ve only seen the movies and I understand the books to be quite different.

The two movies focus on San Francisco teen Mia Thermopolis (Anne Hathaway). Mia is - please read the rest of this paragraph in that enthusiastic surfer voice all 2000s movie commercials used - just a normal teenage girl! When one day the Queen of Genovia (Julie Andrews) visits! Woah! Mia’s the daughter of the recently deceased Prince of Genovia! She has to be the princess now! Dude! Will she be able to balance her new responsibilities with suddenly also being… the most popular girl at school?

Genovia is a fictional country with no 1:1 European analog. It’s supposed to be on the Mediterranean coast between France and Italy, which says it’s Monaco, but everything else about it screams Liechtenstein. It has a queen, a parliament with a prime minister, an economy seemingly centered around pears, and some palace intrigue. The monarch seems to wield real governing power, sits in on parliament, and personally oversees the administration of justice. The movies don’t specify whether Genovia has a constitution, but it sure seems to have I would call this a lightly constitutional monarchy.

Like with most princess media, the form of government here doesn’t really matter to the average viewer. What matters is that Anne Hathaway is beautiful and a princess and you, the school age girl watching The Princess Diaries, want to be her.

No, there will be no overt messaging here. The franchise communicates its Orléanism subtly.

Why do you know this much about The Princess Diaries?

The first film is one of my wife’s favorites. I’ve seen it with her maybe five or six times. Sometimes she puts it on when she needs to power through a monotonous task. She told me I had to watch the sequel before I wrote this piece, so I did. The first one’s a good movie! The second one’s not as good, but I don’t hold that against it. You could put Anne Hathaway in any tween flick in the early 2000s and it would work.

Why do you say it’s Orléanist?

It’s not explicit, but it’s everywhere.

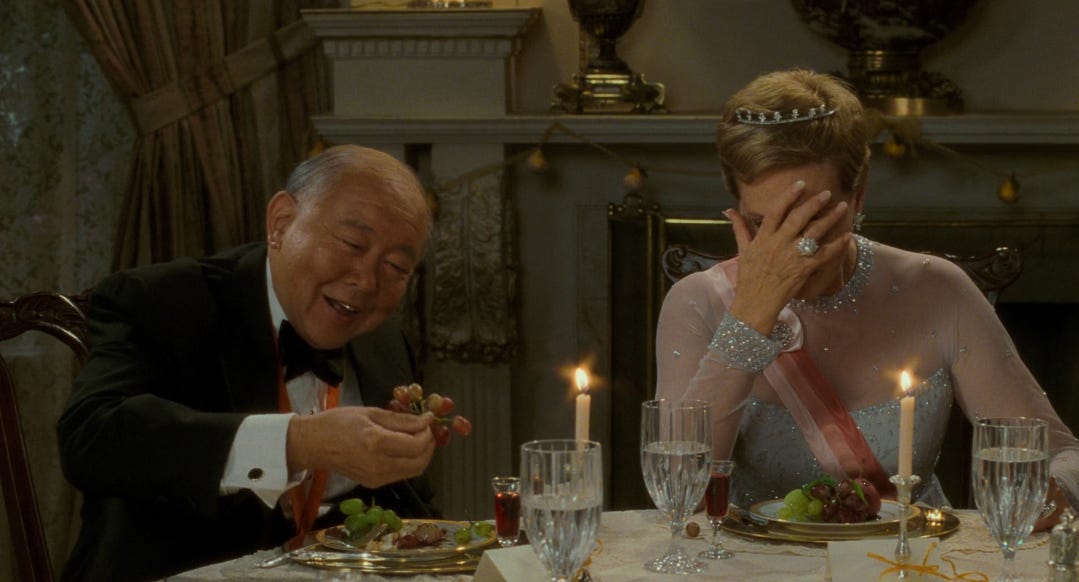

The royal dinner

Take the royal dinner scene from the first movie. Mia, a normal American and a klutz, doesn’t know proper etiquette and stumbles over herself the entire dinner. At one point, she sets a dignitary’s sleeve on fire.

Mia continues to err through the rest of the meal, to great comedic effect.

Other than Mia and Queen Clarisse, we have two Genovian parties at this dinner. First, our secondary antagonists, Baron and Baroness von Troken, who look on at Mia’s antics from across the table in disgust.

The stodgy, traditionalist von Trokens reveal, through a handful of bitter asides, that their family once ruled Genovia but, during a period of political tumult, were forced to step down in favor of the ruling House of Renaldi. Sound familiar?

The other Genovians at the table are Prime Minister Motaz and his wife, literally and figuratively by Mia’s side the entire dinner, helping guide her through the meal. When Mia gives herself brainfreeze with a massive scoop of sorbet, the Motazes follow suit, giving themselves brainfreeze on purpose to divert attention away from the princess.

Prime ministers only exist in systems of government with some form of parliament. Absolutist monarchies generally don’t have them; kings don’t tend to voluntarily cede that much power. But a constitutionalist monarchy would have a parliament and a prime minister because those constitutions almost invariably devolve some power to a legislative branch.2 The dinner literally positions our heroine, with whom the audience is supposed to identify, next to the forces of constitutionalism and opposite from those who claim power on the basis of ancient legitimacy.

But there’s more!

Being American is a positive

At the end of that same dinner scene, Mia accidentally trips a dignitary, causing a chain reaction that sends several waiters to the floor, food into the air, and the queen into a state of disgust.

What a disaster. But wait! A foreign dignitary the queen had failed to impress all night finally opens up, and starts laughing!

The clumsiness is… a positive? It’s just what Genovia needed to keep itself modern? Maybe some (but not all) of the old customs are frivolous? Why, could this film be saying that by importing some aspects of known republic the United States of America, a monarchy can keep itself fresh and nimble? Maybe an aspect like a constitution?

Mia brings social equality

This general pro-American theme persists throughout both films. In The Princess Diaries 2, Mia’s American can-do attitude and sense of universal equality prompts her to stop a parade to prevent an orphan girl from getting picked on.

That’s a classic Orléanist way to present your favored liberal monarch, as the great equalizer and the people’s savior, even if that doesn’t pan out in reality.

Mia goes to college

The bulk of the July Revolution was fought on the streets of Paris by commoners, many former soldiers in the republican and Napoleonic armies, many with much more extreme goals than putting the House of Orléans on the throne. How did Louis-Philippe end up with the crown, then? The university-educated class, that is lawyers, journalists, doctors, businessmen, and so on, agitated Louis-Philippe to accept the throne. Then, the educated class put on a big show in the press, saying that the revolution had been won and didn’t need to go any further.3

The Princess Diaries 2 opens with Mia graduating from Princeton. She didn’t have to go to college. She’s a princess! She’s set for life! Why would she do this? To solidify her caché with Genovia’s educated class, the most ardent supporters of constitutional monarchy, by indicating that she is one of them.

The flag is a tricolor with a royal seal

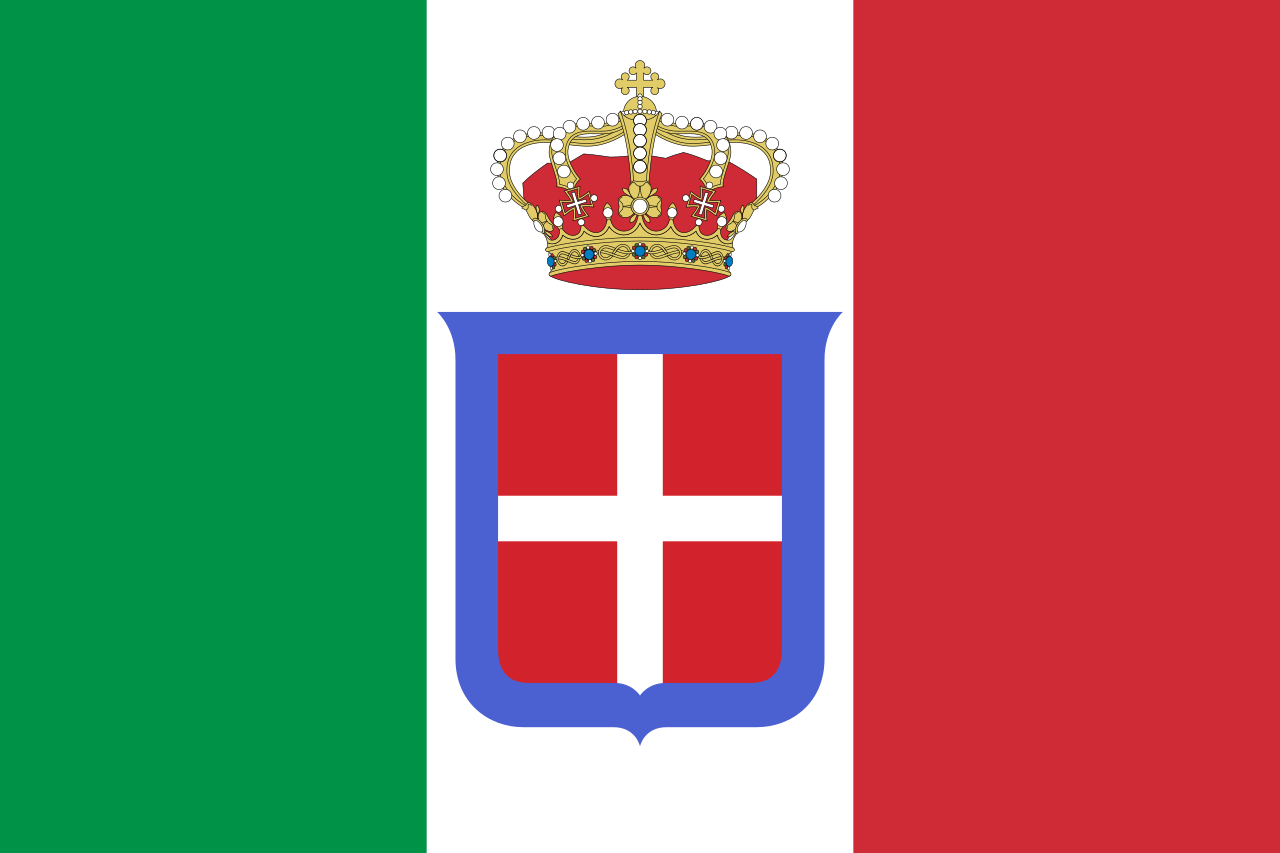

This is my favorite. You saw that flag in the screenshot earlier, right? No, don’t scroll up, I’ll give you a flat image:

That’s a tricolor flag with a royal seal in the middle.

Tricolor flags, as you may know, are classically symbols of republicanism, usually paired with some sense of a national identity. The French tricolor is the most famous, but the German tricolor, Italian tricolor, Irish tricolor, etc. were also all symbols of republican movements within those countries before becoming official national flags.

Louis-Philippe of the House of Orléans, as you now know, cloaked himself in the French tricolor when establishing the July monarchy, making a symbolic appeal to the republican left. He’s not the only constitutional monarch to pull this trick. In pre-unification Italy, the House of Savoy, longtime kings of Piedmont-Sardinia, embraced constitutional monarchy to shore up their bid to unify the Italian peninsula under their rule. This bid worked! The resulting Kingdom of Italy flew this flag.

That’s the Italian republican tricolor4 with the crest of the House of Savoy in the middle. Monarchism with republican tendencies. A constitutional monarchy.

Genovia neighbors both France and Italy. They had to have been influenced by political changes in each country. Like its neighbors once did, Genovia, through distant political tumult, has openly embraced constitutional monarchy.

We’ve established that this is a firmly Orléanist film series, and thus in line with one of the most notable French right-wing traditions. Does that mean the film itself is right-wing?

No.

It’s not right-wing.

Haha! I tricked you! The title was clickbait!

“Left” and “right” are relative terms. In 1793, at the peak of the French Revolution’s radicalism, the ardently republican Girondin faction sat on the right. In the restored Bourbon monarchy’s Chamber of Deputies, a liberal constitutional monarchist might’ve been considered “far left”.

In The Princess Diaries, political conflict occurs between our heroes, Orléanists, and our villains, always right-wing Legitimists. It’s the same each time. In the first movie, our villains in political struggle come from the House of Troken, who (as mentioned above) were an old Genovian ruling dynasty that had fallen out of power. The von Trokens hoped that Mia would reject the throne so that it may fall to them. In the second movie, it’s Viscount Marby, who attempts to elevate his nephew to the throne on a legalistic and Legitimist basis.

The filmmakers even give us visual clues for how we should imagine Legitimism: Like our villains, balding, ugly, and old.

The film attempts no such critique of republican ideologies to its left. At most, Lilly Moscovitz (Mia’s best friend) embodies some modern progressive tendencies, but her character really functions more as a foil to the madness of sudden notoriety, bringing both Mia and the viewer back to a normal high school life.

The films are constitutional monarchist, yes, but they make the case for constitutional monarchy exclusively through contrast with Legitimist movements. The critique is coming from the left (relatively speaking) to the right. These movies are all 1789 and 1830, and not at all 1792 or 1848. It’s not really a right-wing franchise.5

Why did Disney make an Orléanist film?

Was this all intentional? I don’t think so. I don’t think any of it was, really. The filmmakers (and before them author Meg Cabot, who wrote the books) wanted to entertain a teen audience first and foremost. They wanted a story about a princess as they exist in the popular imagination, a beautiful young woman with great dignity, and with some real power for plot reasons. They also wanted the target audience, young Americans learning the republican values of the American Revolution in school, to instinctively root for the main character. They needed a monarchy, they needed a republic.

Thus a conflict between two forms of government that once played out on Parisian streets instead played out in writers’ rooms. Just like in real life, the result was compromise, Orléanism. And when they reached for props and decoration, they used as inspiration the symbols of the compromises once brokered in blood across Europe.

Try all you want. You can’t escape history.

According to French historian René Rémond. I didn’t come up with this three-part division of the French right, it’s famous and famously Rémond’s.

Also, I should mention that strictly speaking these movements just indicate supporters of that family lineage. There was a very far right movement in France in the early 20th century called “Action Française” that had an ideology I’d associate with Legitimism, but formally supported the House of Orléans’ claim to the throne, in large part because the legitimate Bourbon heir was by that time also the king of Spain. Why that would be intolerable, I will leave as an exercise for the reader.

I am not using these definitions that way. When I apply the adjective “Orléanist” here I use it to mean “Constitutional Monarchist” regardless of the recipient’s opinion on the House of Orléans. Similarly, “Legitimist” here really means “Absolutist”. I just think the French context makes it all more fun.

Indeed, the Genovian parliament, complete with silly costumes, plays a major role in the second movie.

What really sealed the deal was the Marquis de Lafayette (yes, the same one that fought alongside Washington in the American Revolution,) known republican and leader of the French National Guard, publicly embraced Louis-Philippe and gave the new king’s ascent his blessing.

Specifically the old flag of the Cisalpine republic, established by France during the coalition wars. There were other Italian republican tricolors, like the blue, red, and black of the Carbonari. No, I won’t explain any of this further.

There’s also the point that we’re considering “left” and “right” purely on the basis of the desired form of government, what 19th century Europeans would call the “Political Question.” Over the course of the century we would also see the “Social Question” emerge, i.e. what to do about discrepancies in social class, the debate that would give socialism its name.

Thanks for knowing this much about real things so you can entertain us about fake things.

(edit: this comment is our most popular thing on Substack lol. We invite you to read our latest short story- about looking down the gap between who you are and who you seem to be: https://open.substack.com/pub/malleablebrains/p/a-common-connection?r=6oyaog&utm_medium=ios

This post sent me down a legitimist Wikipedia rabbit hole, and I would just like to point out that this individual is neither bald nor ugly: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Alphonse_de_Bourbon